by Brooke Peipert

1) When did this project officially begin? And 2) What inspired this project?

The Community Portrait Project (CPP) began in March of 2018, as I was working on some large scale (8ft) commissioned paintings of Alton’s past historic citizens. These were people who had contributed to the betterment of the community but had passed away relatively unnoticed. So often the noteworthy people of our past are depicted so heroically that they become characterless archetypes rather than real people. This deprives us of any genuine connection to them. My goal was not to create idealized historic portraits but to create an emotional bond between our past and present citizens. And so, I painted these faces with the sort of affection and intimacy one feels when sitting relatively close to another, sharing conversation, and making meaningful eye contact. The expressions on these historic portraits are intimate, informal and friendly, to make them relatable. While painting the historic portraits, I recognized what a shame it was that I was paying tribute to people who had not lived to see themselves given the recognition they deserved. And so, I decided upon completion of the historic portraits that I’d paint the contemporary citizens of my community who made Alton a better, more interesting place. It seemed like a good idea to celebrate people while they were alive to appreciate it.

My motivation in creating this community portrait project is twofold; on one hand, in a very basic way, I want to create an opportunity for the people in my community to feel “seen”, to feel recognized for their contribution to the community, whether it is for civic engagement, volunteerism, contributions to the cultural landscape or simply providing moral support or inspiration to others. In a larger sense, these portraits aren’t just about commemorating people for their good deeds alone. They are also about painting the inner life of the models and creating an emotive connection with the viewer, a sense of familiarity and emotional intimacy; something I think our contemporary society shies away from.

So often these days, we spend too much time buried in the false “faces” of our phones, thereby losing the potential to make meaningful contact with others, especially those outside our sphere. I want to try and break that habitual aversion of the eyes that we do occasionally when we see someone in public and avert our gaze instead of making tangible eye contact. I want to create paintings that make eye contact a “do-able” thing, and encourage more of it in real life, beyond the paintings.

Most of all, I want to depict the common humanity within us all, to encourage people to exercise more face-to-face contact which generates more compassion, more dialogue, more interaction with those we are unfamiliar with. Familiarity dispels fear, hatred, and pre-judgement.

How do you choose your models?

When I first began the portrait project, I considered a few acquaintances I knew from around town. Soon enough, however, I found myself watching people, strangers mostly, and finding a certain “energy” some people seemed to exude. I went to a fundraiser and saw a regal looking older woman wearing a rust colored shawl and the most elegant gray hair so elaborately curled that she seemed to have stepped out of a Renaissance painting. After approaching her and asking if I could paint her, her response was so warm and receptive that I started approaching more people I did not know; a local barber who possessed this energy, a young mother who does community work for children in need, spiritual leaders, atheists, young people, old people, those who are wealthy, those who are poor. Instead of looking for traditionally accepted standards of popularized beauty, I sought out my own standards of beauty that were based more on the life and energy within each model I chose. Many of my choices became an intuitive process.

How are the portraits alike? How are they different?

How are the portraits alike? How are they different?

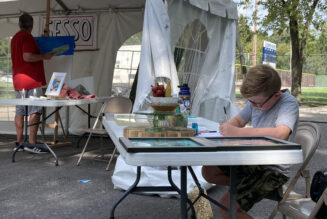

Every person is different and so my approach to painting is different with each painting. As far as similarities go, I typically have an initial meeting with each model, and then a studio visit. Ordinarily, I’d paint from life and have each model sit for me, but because of the high number of people I’m painting, I’m documenting each of the models with roughly 40-60 photos. The photos are not an end product; they are used as an anatomical reference. I don’t paint or copy from a single photo, I create a sort of structural hybrid from 6-8 photos that I consult. I’ve no interest in simply copying a photo in paint. After shooting photos, I meet each model again to interview them about their lives. As I talk with them, I take notes and observe mannerisms and listen to what they verbally express to get a better idea of them as a person. It’s a somewhat lengthy process but I feel it helps me know them a bit, in order to paint them with any genuine honesty. I do not use projection devices and prefer to freehand the mapping out of each portrait. My entire process is very low tech which I enjoy.

The one thing all of my models have in common is that none of them have ever been painted before. I like this. Each model has their own unique response to their finished portrait.

How many portraits will you ultimately paint?

I honestly don’t know. Including the 3 large scale pieces, I painted 18 portraits which were part of the first Community Portrait Project exhibit in April 2019. I’m currently working on roughly 20 more for the next exhibit, early Spring 2020. If everything is still working, I’d love to do a third exhibit with 20 or more portraits late in 2020. Maybe I’ll wind up with between 75 and 100 painted portraits when I’m done.

I’m also writing a book about the Community Portrait Project itself, which will describe the concepts motivating the project and mini bios of each of my models.

One aspect of the project I’ll be detailing in the book is something of an unexpected byproduct of the work, which has been an increasing circle of people I’ve gotten to know by simply reaching out to strangers; many of whom have become friends. I’m also finding myself working as a volunteer within the realm of community work of some of my models as well. The other element in this portrait project has been the interaction of the public with the models themselves. At the exhibit opening, attendees were interested in meeting the models, talking with them a bit, too. The models became like community “celebrities” in a sense, becoming more recognized for what they do, and inspiring others to roll up their sleeves and get more involved in their community, even if it’s simply to broaden their circle. So often we exist within insular realms of Facebook, or Instagram where we collect 1,000 “friends” without truly knowing most of them. My hope is to create a low-tech, indeed a no-tech, forum for basic human interaction between my models and I, my models and their audience, and my paintings themselves and their audience. My hope is that my interest in the inner life of my models is communicated effectively enough in the paintings that the audience feels some emotional connection to them.

What has been the response to the project?

Public reception to the Community Portrait Project has been positive and supportive, indeed I was surprised by the attendance at the first exhibition opening. I’d expected maybe 20 to 30 people to attend, instead over 200 came. The local media has been exceptionally supportive as well. I feel honored to be doing this project, painting my community members, befriending them and learning about their lives. My hope is that this project will help me to be a better artist, a better writer and possibly a better person from my association with so many inspiring individuals I’m painting.

Any negative reception to the project?

At the risk of sounding like some sort of Pollyanna figure who sees only sunshine, I have to admit there’s been no genuine negative reaction to the project. The closest thing to negativity isn’t really negative; it’s more about me learning along the way how to manage my model’s expectations as to what a painting is compared to a photograph. In a painting, the artist interprets the subject matter, in this case the model. A painting is by no means a photograph, nor is it a glamour shot, or something akin to the multiple filtered photos one can post on social media; the kind of filters that make everyone look like soft butter, instead of flesh and bone.

What were your goals for this project?

At the inception of this project, I hoped to make paintings that would offer some respect, admiration and affection to the many people who operate under the radar, doing good things not for applause, but for the simple virtues of altruism and civic engagement. I hoped to acknowledge these people in a way that spoke more informally, as a means for both me and my audience to connect with them, to be inspired by them and to see some shared humanity, which seems vital, especially in a world as divided as ours is today.

We often talk of community building as either an economically motivated enterprise or as a singular event intended as a preventative to poor community relationships. I feel the Community Portrait Project is a vital, ongoing component in building genuine civic pride; pride which is unique to each individual citizen, and providing a forum in which people are given a more lasting recognition for their talents and their contributions to our community.

Where do you see yourself in ten years?

I see myself writing, painting, engaged in my community and traveling.

Where do you see this project in ten years?

Where do you see this project in ten years?

I’d like to see the portraits with a thoughtful caretaker and in a good place where they might be seen as a time capsule, of sorts, of the community at this moment in history. I’d like to see my book about this project be kept within this same realm.

What is your background in the arts?

I received my Bachelors Degree in Fine Arts from Washington University and my Masters Degree from Vermont College of Norwich University. Professionally speaking, I was a college Fine Arts, and Art History professor for 20 years, largely teaching Figure Drawing and anatomy, also painting and art history. I’ve been a practicing artist since 1980, although truthfully, I cannot remember a time in my childhood when I wasn’t drawing.

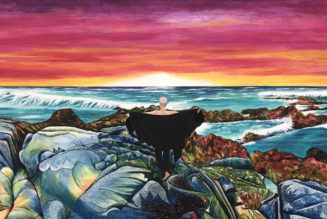

As far as painting goes, my background is in oil painting, but for reasons due to ventilation in my current studio, I started using acrylic paint. I’ve developed a method using acrylic in the same way I’d use oil, building up as many as 15-20 layers of exceptionally thin transparent paint. I’m also using a water based acrylic varnish as well.

People have often asked why I’m painting everyone in shades of blue. As a painter, I’ve always used blue as a base coat for underpainting when I paint people. On top of this blue I’d typically layer other tones to match the actual colors of the flesh of my model. The blue tone acts as a basis for structural shadows which occur in the face. Blue is a color which exists to some degree in all flesh tones, regardless of race and so blue became a conceptual unifier of all the models I’ve painted, regardless of the varying flesh tones each model possessed. I also like the look of black and white films and photography. In a painting, simple black and white can appear flat, whereas blue and white has a bit of an emotional connotation to it. It’s soft, it’s peaceful and somewhat intimate. Some have said the blue is a bit romantic as well. I’ll take it.

What is your favorite work of art?

It’s impossible for me to assign the word “favorite” to any single work of art. In the realm of painting, anything done by the Spanish and Italian painters of the Baroque era is my favorite. Caravaggio, Ribiera, and Velaquez forever will inspire me. In the realm of Baroque sculpture, Gianlorenzo Bernini is one of my favorites. Some of the Germanic painters who’ve inspired me are Lucas Cranach, Lovis Corinth, and Matthias Gruenewald. In the 20th century, I’d throw in Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Willem DeKooning, Lucian Freud, and Max Ernst. No paintings ever made me feel as sultry, stretchy and luxurious as those Matisse paintings he made in Nice, during the 1920’s and 30’s. And on the darker, weirder side of sultry figurative work are the ever inspiring 17th century wax anatomical works in La Specola. In the realm of inspirational sculptural works, my favorites are Martin Puryear, Sue Eisler, Alberto Giacometti, and best of all Louise Bourgeois. In photography my favorites are Brassai, Atget, August Sander, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Mary Ellen Mark, Frederick Sommer, Cindy Sherman and Joel Peter Witkin. As a kid, 1960’s Mad Magazine was a big influence, especially the drawings of Mort Drucker. In the 1970’s and beyond, cartoonist Gahan Wilson was a perpetual inspiration. The silent films of F. W. Murnau, Rex Ingram and Erich Von Stroheim are influential favorites, as is Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. Films from a more modern era include those of Fellini, Tarkovsky, Bergman, Werner Herzog and Alejandro Jodorowsky all of these are my favorites, and all have influenced me in some way or another as an artist.

If called upon, I can create an equally ponderous list of writers and musicians that influence my work as an artist, but at a certain point, no one wants to keep reading lists, do they?

What is your advice to young artists?

My advice to artists is as lengthy as my list of artistic influences.

My advice to young artist is the same advice I’d give older artists, myself included. Take your art education seriously and take it for the long haul; in other words, keep learning for the rest of your life. Whether your education is through college or whether it’s through your own self-guided study doesn’t matter much. As an educator, my prejudice leans to college simply because it exposes you to far more experiences and people than one’s own self-guided education might. But there are exceptions to this, and I’ve known a few artists that were incredible exceptions to this. The point is to keep challenging yourself intellectually, aesthetically and emotionally. Keep developing your craft.

Don’t become an artist in order to be rich and famous. The ratio of rich, famous artists to the number of people making art is one in a million. There are better, more effective ways to become rich and easier ways to achieve fame.

Be willing and able to make 100 works of art in order to create one good one; and most importantly, be capable of recognizing the other 99 works as necessary lessons you needed to learn. Be capable of doing research on any given subject to understand it in order to express it thoughtfully as an artist.

Be open to the influence of the masters, the big guys in art history, but not to merely copy/mimic what they did, but to try to comprehend the ideas behind what they did and why they did it within their social context, and yes, how they did it as well in terms of technical skills. Learn to talk about, write about the ideas behind your own work. Understanding how to communicate your ideas verbally will actually help you come to a better understanding of them. The more informed you are, the more thoughtful and communicative your art works will be.

Banish the phrase, “I know what I like” anytime you are looking at works of art that perhaps you don’t like or understand. The oft-repeated phrase “I know what I like” really means that you like what you know. It’s not a great thing to admit to. It just means you only like what you are familiar with, which is kind of the kiss of death for an artist or any thinking person really. Just because something is unfamiliar or beyond your comprehension doesn’t mean it’s not good, it doesn’t mean it’s invalid. It just means you don’t understand it… not yet, anyway. Perhaps you never will, and that’s ok too. And on that note, if you ever see a work of art utterly beyond your understanding, it’s ok. Not everyone gets every joke, not everyone understands every piece of art. It’s alright sometimes just to look at a work of art and think about how you respond to it, just as it’s ok to sometimes simply appreciate the aesthetics of a piece, even if the conceptual premise of the work evades you.

Look at works of art outside of your area of interest. If you are a traditional landscape painter, look at abstract expressionism. If you are an abstract sculptor, look at Renaissance figurative painting. If you are a ceramicist, look at graphic novels. Expose yourself to works outside of your comfort zone; they have a lot to teach you about visual language, which has no barriers from one form of artistic media to another. No media is superior to others. It’s the thought and talent behind the media that matters.

Stay perpetually open to learning new things, otherwise you will rot from within and no perfume can mask that sort of thing.

Monica Mason – Facebook.com/splonx